Britain vs The Future: A Nation Determined to Modernise, As Long As Nothing Changes

Tradition vs Modernity

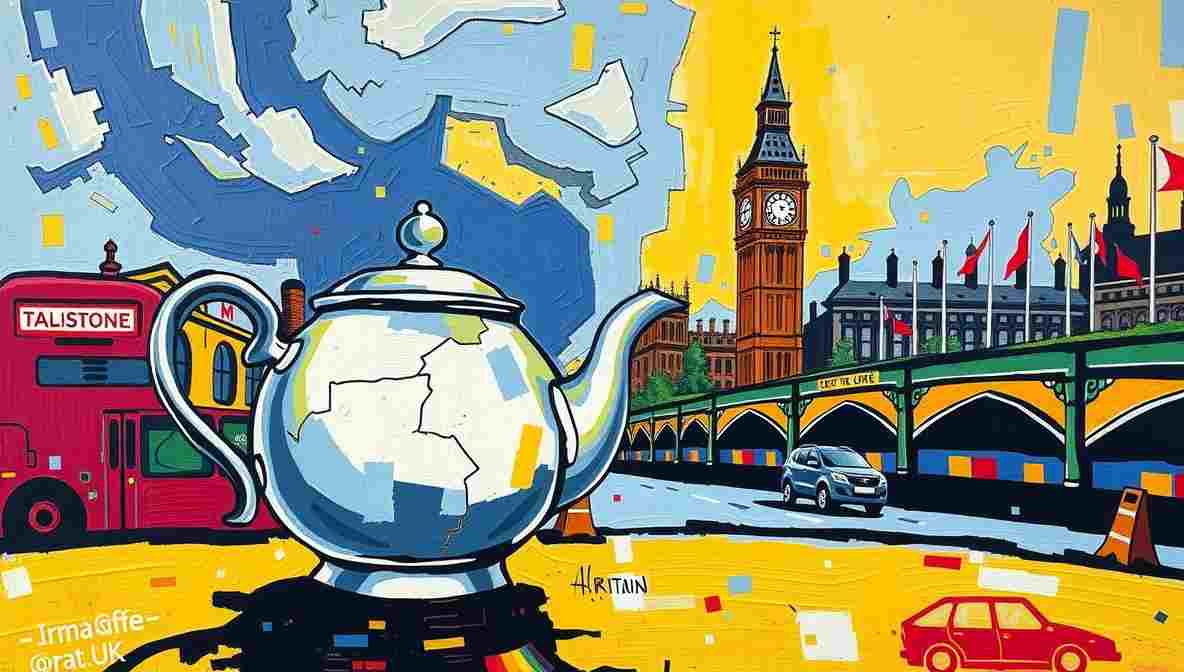

Britain is a country that loves tradition so much it treats it like an heirloom teapot: cracked, stained, never actually used, but absolutely not to be thrown away under any circumstances—probably needs to be dusted occasionally and wept over. At the same time, Britain is desperate to be modern—provided modernity doesn’t interfere with lunch, weather complaints, or the correct way to queue, which is obviously single file, in silence, radiating passive judgment.

This tension between tradition and modernity defines almost every national debate. It is why we have contactless payments but still refuse to throw away receipts “just in case.” It’s why Parliament debates artificial intelligence in a room that looks like it was last refurbished during the reign of someone called Edward—possibly Edward VII, possibly Edward the Confessor, architecture is just kind of sad and old in there.

The British don’t resist change outright. They simply greet it with suspicion, mild irritation, lengthy consultation, and a vague sense that everything was better before, even if “before” was the 1970s and everyone was cold, poor, and miserable.

Tradition: The Sacred Art of Doing Things “Properly”

British tradition is not about efficiency or logic. It is about doing things the way they’ve always been done, even if no one can remember why—which is basically the national motto at this point.

Take the monarchy. Objectively, it is a medieval concept wearing modern tailoring. A family chosen by divine right waves from balconies whilst the public argues about whether the waving angle was “disrespectful to history” or “appropriately enthusiastic for someone whose job is essentially waving.” Any suggestion that this system might be updated is met with the existential question: “Yes, but what would tourists think?”—as if the entire constitutional foundation of the nation rests on whether Americans can take a good photo.

Tradition in Britain survives largely because it’s quaint. It looks good on postcards. It distracts from the weather, which is depressing. It makes Britain feel less like a modern nation struggling with problems and more like a theme park where everything is slightly broken but charmingly so.

And crucially, tradition provides structure. Without it, Britons would have to confront the terrifying possibility of improvisation, which is basically Continental behaviour and absolutely not acceptable.

Modernity: Download the App, Regret the App

Modern Britain arrives mostly in the form of apps that promise to “disrupt” things that were working fine—or, more accurately, things that were working poorly but at least had the decency to involve a human you could complain to.

Want to see a doctor? There’s an app—and a 12-week wait, but at least the app didn’t judge you personally.

Want to pay council tax? There’s an app—which will probably crash on the deadline.

Want to complain about the app? There’s a chatbot that apologises profusely but does absolutely nothing, which is peak British technology implementation really.

Modernity is sold as convenience, but often feels like homework. You are constantly being asked to verify your identity (Are you really you? Can you prove it? Should you be trusted?), create a password (something complex but memorable, which means impossible), reset the password (because you immediately forgot it), confirm the reset (prove you didn’t forget your email address), and then told the service is “temporarily unavailable”—which is British-speak for “we broke it and don’t know when we’ll fix it.”

The British public’s relationship with modern technology is cautious at best, suspicious at worst, and deeply resentful at all times. We don’t fear it—we resent it with the intensity usually reserved for mild inconveniences. The moment an app replaces a human being, the nation quietly mourns the loss of someone to complain to whilst standing in line for 45 minutes.

The Queue: Tradition’s Final Boss

Nothing illustrates the clash between tradition and modernity better than the queue—Britain’s most sacred ritual and probably the only thing uniting the entire nation.

Britain has perfected queuing to an art form that’s basically meditational. It is orderly, silent, and deeply emotionally charged. The queue is not merely a line of people—it is a social contract, a shared understanding that we will all wait in miserable silence, judging each other gently.

Modernity attempted to improve this with digital booking systems (removing human contact), virtual queues (removing any legitimate reason to exist), and “estimated wait times” (which are always wrong). Britain rejected this immediately and completely. A virtual queue offers no eye contact, no shared sighs of resignation, and no opportunity to silently judge someone who joins at the wrong point like some kind of barbarian.

The British queue is democratic—everyone waits equally, everyone suffers equally, everyone leaves slightly resentful. Apps are not. Apps have favorites. Apps are neoliberal chaos.

Any technology that interferes with queuing is viewed not as innovation, but as provocation—a personal attack on British values and the sanctity of orderly waiting.

Tea: Where Tradition Draws a Hard Line

Britain has embraced sushi, oat milk, contactless payments, and cryptocurrency probably. But tea remains sacred—untouchable, inviolable, the last bastion of national pride.

Traditionally, tea is strong enough to stand a spoon in (which makes no practical sense but is how everyone describes it), served in a mug that has survived at least one workplace restructure, one house move, and definitely one incident involving boiling water from which the mug mysteriously recovered.

Modernity has tried to intervene with matcha (grass powder that tastes like disappointment), chai (basically tea but spicy, which is showing off), cold brew (tea, but wrong), and something called “tea pearls,” which Britain has correctly identified as treason against the beverage.

The great British tea debate is not about flavour—it’s about identity. Milk first or last is not a preference—it’s a personality test that determines if you’re civilized or a monster. The water temperature has very specific rules that nobody actually follows. The brewing time is simultaneously flexible and absolutely rigid.

Modern cafés offering “artisanal infusions” (fancy leaf water) are tolerated only because they are easy to avoid. Britain will modernise many things—monarchy, Parliament, workers’ rights eventually maybe—but tea will not be one of them. Tea is where progress comes to die.

The Workplace: From Bowler Hats to Burnout

Traditional British work culture was built on hierarchy, routine, and the firm belief that suffering quietly is not just professional but morally correct. Your pain is your business. Your problems are your shame. Your lunch break should be eaten whilst working because complaining is unprofessional.

Modernity has introduced flexible hours (nobody takes), open-plan offices (where everyone pretends to work whilst desperately avoiding eye contact), and the radical idea that work should be fulfilling. Britain has accepted these concepts in theory—in company emails and wellness seminars—whilst quietly continuing to work through lunch, skip breaks, apologise for existing, and treat any enjoyment of work as suspicious.

Open-plan offices were meant to encourage collaboration. Instead, they created a nation of people pretending to be busy whilst desperately avoiding eye contact, setting up small fortress-walls made of monitors and stationery, and scheduling back-to-back meetings to avoid actual work.

Remote work terrified Britain at first—pure panic. Without offices, how would managers know people were working? How would they see you suffering? Eventually, the nation adapted, discovering that productivity could exist without commuting, and in fact productivity improved without commuting. But still—still—insisting on video meetings that could absolutely have been emails.

Language: Keep Calm and Update Your Vocabulary

British tradition treasures language. Polite understatement (saying “that’s not ideal” when meaning “this is a catastrophe”), passive aggression (the national love language), and the word “quite” meaning seven different things depending on tone and whether you sound disappointed.

Modernity has introduced new vocabulary: “impactful” (having impact, which is redundant), “leveraging” (using, but with more syllables), “circle back” (let’s continue this conversation later, meaning never), “synergy” (something that sounds important but means nothing). These words have been politely acknowledged and then immediately mistrusted by British culture, which suspects them of being American lies.

The British language evolves slowly, suspicious of enthusiasm. Americanisms arrive (like “y’all”), are mocked relentlessly (like “y’all”), and then quietly adopted years later (somehow “y’all” is now in British usage)—while Britain pretends this was always the case and definitely not because American media conquered our consciousness.

Texting has shortened communication to fragments, emojis, and chaos. But British politeness remains intact. Even messages ending in “Sent from my phone” feel apologetic, as if you’re personally apologizing for technology’s limitations.

Fashion: Tweed Meets Streetwear

British fashion is a paradox that would confuse anyone trying to understand it. It celebrates tradition (Savile Row tailoring, sensible shoes, clothes that last decades) whilst constantly reinventing itself (trainers that look like alien spacecraft, whatever the youth is wearing).

One moment, Britain is proud of heritage tailoring and proper dress codes. The next, it’s wearing technology-designed footwear and ripped jeans that cost more than actual functional jeans.

Modern fashion trends are welcomed cautiously, usually after someone famous wears them and apologises for the audacity. Anything too bold is labelled “a bit much”—which is British for “this doesn’t feel sufficiently apologetic.”

Traditional British fashion prioritises preparedness and durability. A proper coat must survive rain, wind, awkward funeral encounters, and at least one completely unexpected crisis. Modern fashion may look good on Instagram, but Britain values pockets—especially women, who are just discovering that clothing could be functional.

Transport: The Past, Delayed

British transport is where tradition and modernity actively fight each other on packed trains without anyone making eye contact about it.

The railway system was once the envy of the world—pioneering, innovative, reliable. Now it is a heritage experience where delays are announced with historical pride and apologies that assume you should be grateful the train arrived at all.

Modern ticketing systems exist (several competing ones, naturally), but still require three different cards, a barcode, and an argument with a gate that’s confused about whether you’re a valid passenger. Britain wants high-speed rail, but only if it doesn’t disturb anything built after 1066 or require any actual disruption.

Cycling lanes appear overnight, confusing drivers and cyclists equally in a spectacular display of poor planning. Electric scooters are introduced (chaos), banned (order), reintroduced (why?), and then politely ignored (everyone agrees this was a bad idea).

Transport in Britain is not about speed. It is about endurance—how long can you stand this nightmare before you just accept it?

The Pub: Tradition’s Last Stand

The pub remains Britain’s strongest resistance to modernity, a final fortress where tradition still rules and nobody has to apologize for drinking at 3 p.m. on a Wednesday.

Whilst gastro pubs and cocktail menus have emerged (and been tolerated grudgingly), the heart of the pub remains unchanged: sticky floors (are they dirty or is this character?), unclear rules (did I order correctly? Will I be judged?), and at least one man who has been there since the 1980s, nursing a pint that may be the same one from 1987.

Apps have tried to modernise pub ordering (efficiency!). Britain rejected this immediately. Ordering at the bar is ritual—it involves eye contact with someone who might judge you, patience whilst waiting for service, and the fear of being skipped because you don’t look local enough.

Modern pubs offer vegan options (why?), craft beer (pretentious but acceptable), and ambient lighting (depressing). Traditional pubs offer judgment, crisps, and a sense of community built entirely on shared misery.

Both coexist uneasily, united only by the shared belief that pubs should not play music too loudly and that anyone who tries to change that is objectively wrong.

News, Social Media, and the National Opinion

Traditionally, Britain got its news from newspapers that told it what to think with complete authority and absolutely no fact-checking.

Modernity replaced this with social media, where everyone tells everyone else what to think at once, immediately, and usually angrily. This is progress, apparently.

British satire thrives in this chaos. The nation distrusts institutions (they’ve earned it) but also distrusts influencers (they haven’t earned anything). Everyone is suspicious of motives, including their own motives, which is very British.

The British response to modern outrage culture is largely exhaustion—pure fatigue. Public apologies are watched carefully (looking for insincerity), judged harshly (because they’re always insincere), and then immediately forgotten (because there’s a new scandal in 20 minutes).

Tradition vs Modernity in Politics

British politics is essentially tradition and modernity arguing with each other whilst pretending to agree for the cameras.

Parliament is a modern legislative body operating in a room designed for candlelight and horses, with furniture that looks like it’s actively rotting. MPs tweet in real time (modernity!) whilst wearing expressions that suggest they disapprove of electricity and definitely electricity as applied to communication.

Reforms are proposed, debated extensively, delayed for no reason, reviewed by someone who doesn’t understand the issue, reconsidered by the original people who already made a decision, and eventually forgotten entirely. This is not inefficiency—this is tradition masquerading as deliberation.

Modern political branding clashes catastrophically with British scepticism. Any slogan that sounds too confident is immediately mistrusted—”Get Brexit Done” was too confident, so they did Brexit worse. “Strong and Stable” got ridiculed. Anything that sounds like it actually knows what it’s doing will be rejected.

Why Britain Can’t Let Go—And Shouldn’t

The joke, of course, is that Britain needs both tradition and modernity—in tension, in conflict, arguing constantly.

Tradition gives identity (we know who we are), continuity (it’s always been this way), and comfort (it’s familiar suffering). Modernity provides adaptation (we can learn new things), survival (without it we’d actually perish), and Wi-Fi (without which modern life is impossible).

The tension between them is not a flaw—it is the system itself. Britain moves forward by dragging the past with it, occasionally apologising, mostly complaining, and always—always—drinking tea about it.

This is why Britain still works. Not because it resists change, but because it questions it loudly, sarcastically, and over tea whilst standing in a queue judging everyone around it.

Conclusion: Progress, But Politely

Britain will continue to modernise, but never quickly—never smoothly, probably with arguments the entire way. It will adopt new technology whilst complaining about it constantly. It will preserve traditions whilst quietly bending them when nobody’s looking.

This is not hypocrisy. It is balance—precarious, uncomfortable balance maintained through passive aggression and tea.

A country that can invent the industrial revolution, mock itself endlessly, argue about the correct way to butter toast (butter on first, then jam, obviously), and still debate whether tea should have milk is not stuck in the past—it’s negotiating with the past like a difficult family member at Christmas.

And as long as Britain keeps doing that—awkwardly, sarcastically, with a cup of tea in hand, and someone in the background complaining about the weather—tradition and modernity will continue their uneasy truce.

Which, frankly, is the most British outcome possible.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, there’s an app telling me my train is delayed, centuries-old British instinct is telling me to complain about it forever, and I’ve got a queue to stand in whilst silently judging everyone else’s life choices.

Alan Nafzger was born in Lubbock, Texas, the son Swiss immigrants. He grew up on a dairy in Windthorst, north central Texas. He earned degrees from Midwestern State University (B.A. 1985) and Texas State University (M.A. 1987). University College Dublin (Ph.D. 1991). Dr. Nafzger has entertained and educated young people in Texas colleges for 37 years. Nafzger is best known for his dark novels and experimental screenwriting. His best know scripts to date are Lenin’s Body, produced in Russia by A-Media and Sea and Sky produced in The Philippines in the Tagalog language. In 1986, Nafzger wrote the iconic feminist western novel, Gina of Quitaque. Contact: editor@prat.uk