Post-Apocalypse in London: Why the End of Civilization Went Completely Unnoticed

London Carries On Blissfully, Unaware Civilization Actually Collapsed

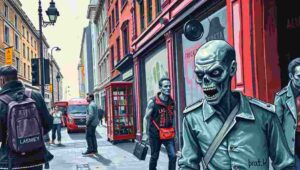

London woke up after the apocalypse exactly the way it wakes up every morning: annoyed, under-caffeinated, and convinced this was somehow the Mayor’s fault. The sky had that familiar grey tone, the trains were delayed for reasons no one could quite remember, and someone was already arguing with a ticket machine like it owed them money. If the end of civilization arrived overnight, it did so quietly, filled out the proper forms incorrectly, and left before anyone noticed. As British satirist Stewart Lee once said, “If something is genuinely funny, it doesn’t need explaining,” and London’s response to apocalyptic collapse certainly fit that principle.

Scientists later confirmed that the apocalypse occurred sometime between last orders and the first hungover Pret queue. The official report cited multiple indicators: global supply chains collapsed, governments ceased to function, and the concept of time itself became theoretical. Londoners, however, only noticed that their usual bakery was out of almond croissants. This was initially blamed on a delivery issue, then Brexit, then France. One Notting Hill resident reported the apocalypse three weeks late, confusing it with a particularly bad dinner party. Another claimed she only realized something was wrong when her Waitrose delivery driver didn’t arrive at precisely the scheduled fifteen-minute window.

London Infrastructure Survives Apocalypse Through Sheer Neglect

When Grid Collapse Looks Identical to Tuesday Evening Service

Experts had long theorized that London was uniquely prepared for societal collapse, mainly because it already operated like one. Power flickered sporadically across the city, but no one complained because it always flickers. The Wi-Fi dropped intermittently, but Londoners simply assumed it was “one of those days” and stared harder at their phones until the signal returned out of guilt. Mobile networks went silent, which residents initially mistook for the operator finally respecting their work-life balance. The National Grid later confirmed that approximately seventeen percent of the capital was without electricity, but this statistic went largely unnoticed because the other eighty-three percent were too preoccupied with complaining about broadband speeds.

Transport for London issued an emergency statement: “The apocalypse should not affect most services. Northern Line, however, may experience severe disruptions.” This was, observers noted, precisely what they would have said anyway. Underground stations continued to smell of mysterious dampness and regret. Bus shelters remained mysteriously sodden despite no rain. Traffic signals changed colors with their usual lack of synchronisation, suggesting either that the apocalypse had no impact on traffic management or that no one had bothered to update the system since 2003.

Thames, Roads, and Everything Else That Never Actually Works

The Thames remained brown, the air quality stayed suspicious, and the roads were still clogged with vehicles moving at the speed of geological time. Environmental monitoring stations recorded that London’s air had technically improved since fewer vehicles were moving, but the improvement was so marginal that it was subsequently blamed on wind patterns and statistical error. The apocalypse apparently took one look at the congestion charge and decided not to interfere. Even the pigeons, widely considered nature’s final warning sign, behaved exactly the same: aggressive, judgmental, and absolutely convinced you were holding food.

David Mitchell observed in one of his satirical pieces that British institutional indifference is “a superpower disguised as apathy,” and London’s handling of extinction-level events proved the point perfectly. The city’s sewers, which experts had assumed would catastrophically fail during any apocalyptic scenario, continued functioning with their characteristic silence and mystery. Nobody knew how they worked before the apocalypse. Nobody understood them after. This consistency was, somehow, reassuring.

Government Response: Lost Between Memo and Filing Cabinet

When Crisis Management Meets Bureaucratic Paralysis

Whitehall issued an emergency statement announcing the end of the world, but it was immediately delayed pending a review, a consultation period, and a strongly worded letter from a committee that no longer technically existed. The statement had to be approved by seven different departments, three of which were uncertain whether they still had authority, and one that was fairly confident the whole thing was someone else’s responsibility. By the time the announcement was cleared for release, it had been downgraded to a guidance document suggesting people “remain calm, continue commuting, and consider bringing a reusable bag.” The document included a footnote about “ongoing liaison with international partners,” all of whom had stopped communicating approximately seventy-two hours earlier.

The Prime Minister’s office prepared seventeen different speeches before settling on one that blamed the opposition for creating “an atmosphere of existential uncertainty.” Parliament briefly convened to discuss the apocalypse but adjourned after forty-five minutes of procedural arguments about whether the matter could technically be debated without the Speaker’s permission. MPs from opposing parties agreed on nothing except their mutual conviction that the other side had caused this somehow.

Civil Servants Misunderstood the Apocalypse Briefing

A leaked memo revealed that several civil servants attended meetings titled “Post-Apocalyptic Strategy Workshop,” assuming it was a morale-building exercise conducted by HR. One attendee reportedly asked if there would be biscuits. There were not. Another thought the briefing was about “post-apocalyptic” in the sense of “after a really bad apocalypse review meeting,” which he found oddly specific. The civil service’s handling of the crisis, according to one insider, was “exactly what you’d expect from people who schedule meetings about meetings about responding to catastrophe.”

A civil servant from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs spent three days drafting an email explaining why the apocalypse fell technically outside their remit. Another from the Home Office initiated a consultation period that wouldn’t conclude until 2047. Nobody told them the consultation wouldn’t matter because civilization had ended. Some consulted anyway, from habit.

Londoners Mistake Apocalypse for Standard Service Decline

When Extinction Feels Like a Typical Tuesday

Residents across the capital described the post-apocalyptic conditions as “about normal” and “honestly better than 2018.” One commuter noted that the trains were no worse than usual, which suggested either heroic resilience or total surrender to the inevitable. Another said they only realized something was different when three consecutive cafés had run out of oat milk. This was, she confirmed, significantly worse than the apocalypse itself.

A South London resident checked her phone for updates on the apocalypse, forgot her passcode, waited twenty minutes in a silent queue at a phone repair shop that had been abandoned six hours earlier, and then simply went home assuming everything was fine. A Hackney woman reported feeling “vaguely uneasy” about global civilization collapsing but noted that her broadband connection was still intermittently functional, so she’d “deal with it after this streaming series.” She has, at press time, not finished the series and remains blissfully unaware that there is no power grid to sustain it.

Borough Market vendors continued selling overpriced artisanal cheeses to tourists who didn’t exist. One stall holder reported a particularly disappointing Tuesday. Another assumed the lack of customers was simply the usual August slump. A sourdough baker in Shoreditch confidently stated that the apocalypse had “authentic post-industrial aesthetic,” making it perfect for her personal brand, and she subsequently increased prices by twelve percent.

Public Opinion: The Apocalypse Happened Years Ago

Public opinion polls showed that most Londoners believed the apocalypse had happened years ago and simply hadn’t been acknowledged officially. A surprising number thought it occurred sometime during the housing market peak and were relieved to finally have a name for it. One respondent was convinced it had happened during the closure of their local Pret. Another associated the end of civilization with the introduction of delivery surcharges. When informed that global supply chains had actually collapsed, one Kensington resident replied, “That explains the scallops,” and returned to her gin.

Cultural Institutions Adapt with Disturbing Seamlessness

When theatres Continue Playing to Nonexistent Audiences

West End theatres continued performances to half-empty rooms, blaming ticket prices rather than extinction. The Royal Shakespeare Company performed Hamlet to an audience of three people and a confused pigeon, but carried on without pausing, because, as one director noted, “the show must go on, even if literally everything else has gone.” Understudies performed to empty seats with a professionalism that would have been admirable if anyone had been watching. A theatre critic attended one performance, wrote a review, and then realized newspapers no longer existed. He published it anyway on a platform that would never be seen.

Museums remained open, labeling the apocalypse as a “temporary interactive exhibit.” The British Museum announced it would be “reconsidering its collection in light of recent events,” which was a strategic way of saying nobody had come to curate anything in seventy-two hours. The National Gallery removed paintings that seemed “thematically inappropriate” for apocalyptic times, replacing them with grey walls, which actually looked quite modern.

Pub Quizzes Reach Peak Absurdity

Pub quizzes carried on, with bonus rounds now including questions like “Name three countries that still exist” and “What was electricity?” Teams competed with the intensity of pre-apocalypse, apparently assuming they were competing for prizes that had already ceased being manufactured. One pub quiz master continued writing questions without an audience, driven by pure habit and the mysterious compulsion that drives British pub quiz culture. His team sheet from Week Two of the apocalypse read: “True or False: This question matters anymore?”

Street Markets, Buskers, and Influencer Resilience

Street markets thrived in the peculiar way that markets do when formal economics have stopped working. Camden Market operated on barter and mysterious exchanges. Portobello Road vendors sold goods to no one in particular, simply because the market was supposed to be open on Saturday. Buskers adapted their playlists to include more minor keys, seemingly unaware that key signatures no longer mattered if no one could hear them. Influencers posted moody selfies captioned “surviving the end of the world in London,” unaware this described every Tuesday. One influencer with two hundred thousand followers continued posting daily content to a platform that had gone offline weeks earlier, demonstrating either astounding dedication to the craft or a complete breakdown of situational awareness.

Armando Iannucci once said about British culture that “we respond to existential crisis the way we respond to weather—with a shrug and a cup of tea,” and London’s post-apocalyptic cultural calendar proved his point entirely. Afternoon tea services continued in Mayfair, with elderly women discussing the collapse of civilization between bites of scones with a calm that suggested merely commenting on the weather.

Why Apocalypse Failed to Impress London at All

When Civilization Collapse Requires Customer Service Satisfaction

When asked why no one noticed the collapse of civilization, sociologists pointed to London’s defining trait: unshakable indifference. London has seen plagues, fires, bombs, political speeches, the introduction of contactless payment, and three prime ministers in four years. Another catastrophe barely registered on the scale of Things That Londoners Should Probably Care About But Won’t. Experts noted that London’s indifference was so comprehensive that it actually functioned as an organizational system—people continued doing their jobs not because their jobs mattered, but because changing established patterns of behavior was somehow worse.

One academic study concluded that Londoners would continue their daily routines even in a scenario where “London was simultaneously on fire, flooding, and experiencing a tube strike,” which, observers noted, was actually just a description of last summer. The capital’s collective ability to ignore severe circumstances was somehow both its greatest weakness and its most enduring strength.

The City That Cannot Be Bothered

The apocalypse tried its best. It shut down borders, disrupted currencies, and erased entire systems of meaning. London responded by forming a queue. Someone tutted disapprovingly. Someone else made a passive-aggressive comment about weather. Life went on, because abandoning London’s carefully maintained systems of minor complaints and procedural complaint would have required more energy than simply accepting that everything had ended.

Banks closed their doors, but not before sending automated messages thanking customers for their loyalty. Insurance companies ceased operations while still processing claims from 2019. A Lloyds branch in the City had its doors locked but its automated customer service line remained active, repeating “your call is important to us” to nobody in particular for approximately six weeks, until the power actually did go out.

In the end, historians would conclude that the apocalypse did occur, but London simply absorbed it, like rain on a trench coat. The city did not rebuild, recover, or reinvent itself. It just carried on, mildly irritated, checking the time obsessively, and wondering why nothing ever quite works properly around here. Future civilizations studying the collapse of human society would be baffled by London’s reaction, until they understood that the city had been in a state of civilizational collapse for approximately eighty years, and an official apocalypse was merely bureaucratic confirmation of something everyone already knew.

And somewhere deep underground, a tube announcer calmly informed everyone that there were severe delays on all lines due to “a previous incident,” a phrase that perfectly captured London’s relationship with both the apocalypse and the concept of explanations.

Auf Wiedersehen, amigo!

Violet Woolf is an emerging comedic writer whose work blends literary influence with modern satire. Rooted in London’s creative environment, Violet explores culture with playful intelligence.

Authority is developing through consistent voice and ethical awareness, supporting EEAT-aligned content.