Royal Vauxhall Tavern: Where Drag Queens Invented Modern Politics

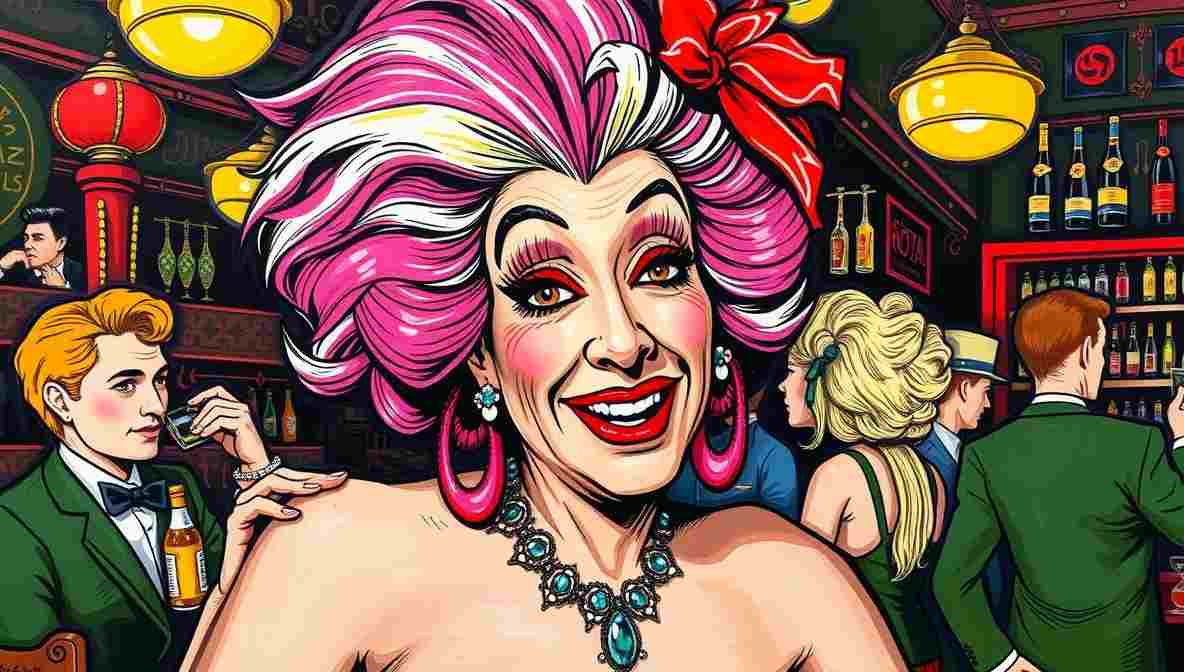

The Royal Vauxhall Tavern has been serving camp, chaos, and revolutionary politics since 1862, making it older than most British institutions and significantly more entertaining than all of them. This Grade II listed LGBTQ+ heritage site in South London witnessed the drag revolution before anyone realized revolutions could involve sequins and death drops.

The Venue: Victorian Architecture Meets Postmodern Gender Theory

The RVT occupies a corner plot in Vauxhall that’s seen more political awakenings than Westminster. The building survived two world wars, the Blitz, and Margaret Thatcher—though the last one was touch and go. Its survival as an LGBTQ+ space through decades of persecution represents Britain’s most successful long-term resistance movement, assuming you ignore the NHS.

“The Royal Vauxhall is where British queerness learned to fight back while wearing heels,” said Paul O’Grady, who performed as Lily Savage there for decades.

The Audience: Everyone Who’s Anyone and Everyone Who Isn’t

RVT crowds include drag queens, activists, celebrities slumming it, and confused tourists who thought they were entering a normal pub. It’s the only venue where you might find Freddie Mercury, Princess Diana, and local council estate residents sharing the same dance floor—usually not simultaneously, but the possibility existed.

“Playing the Vauxhall means your act needs to work for everyone from working-class South Londoners to international superstars in disguise,” said Graham Norton, who understands the demographic impossibility.

The venue’s bathrooms contain more political graffiti than actual graffiti, with messages ranging from revolutionary manifestos to phone numbers for questionable services. It’s democracy expressed through Sharpie markers and architectural vandalism. The LGBTQ+ rights movement was partially organized in these toilets, which should probably be mentioned in history textbooks.

“I’ve seen better political discourse in the RVT loos than in the House of Commons,” said Sandi Toksvig, who’s experienced both.

The Drag Revolution: When Camp Became Weaponized

The RVT pioneered drag as political resistance long before it became mainstream entertainment. During the 1980s AIDS crisis, drag performers turned the venue into a community center, fundraising operation, and mental health facility disguised as a nightclub. They provided support, solidarity, and spectacular entertainment while the government pretended the crisis didn’t exist—a strategic failure that killed thousands.

“We were saving lives while wearing wigs—try doing that in your office job,” said Baga Chipz, representing the next generation of RVT performers.

The Police Raids: When Authority Met Sequins

The RVT survived multiple police raids during decades when homosexuality was illegal, then criminal, then tolerated, then eventually accepted. Each raid strengthened the community’s resolve and improved their contingency planning. By the 1980s, regulars had escape routes planned with military precision—though running in heels requires skills most military training doesn’t cover.

“Getting raided by police became part of the show—terrible for civil liberties, great for crowd bonding,” said Julian Clary, who remembers the era vividly.

The venue’s political resistance wasn’t theoretical activism—it was survival disguised as entertainment. Drag performers used camp humor to process trauma, build community, and challenge the heteronormative assumptions that Section 28 tried to legislate into permanence. Every performance was an act of defiance, every laugh a small victory against oppression.

“Camp isn’t just aesthetics—it’s a survival strategy that happens to look fabulous,” said Alan Carr, explaining the philosophy.

The Performers: Activists in Makeup

RVT drag performers weren’t just entertainers—they were political operatives who happened to tell jokes between advocating for human rights. Lily Savage raised consciousness and bar receipts simultaneously. Regina Fong challenged gender norms while lipsyncing to Diana Ross. The venue created a space where politics and performance merged into something resembling art, activism, and absolute chaos.

“Drag at the Vauxhall was never just drag—it was revolutionary praxis in a cocktail dress,” said Sue Perkins, who witnessed the movement firsthand.

The Material: Subversion Disguised as Entertainment

RVT performers perfected the art of saying radical things while audiences laughed too hard to realize they’d just experienced political education. Jokes about Thatcher, AIDS policy, and systemic homophobia weren’t just comedy—they were resistance literature performed to disco beats. The venue proved that humor could be both hilarious and politically devastating, a combination most politicians still haven’t mastered.

“We told jokes that would get you arrested if you said them seriously—camp provided plausible deniability,” said Paul Sinha, who appreciates the strategic brilliance.

The RVT’s influence spread beyond comedy into mainstream culture. Television producers attended shows and commissioned their own. Performers like Lily Savage transitioned from underground icon to national treasure. Drag went from criminal activity to prime-time entertainment, though the journey took decades and required more casualties than anyone wants to count.

“The Royal Vauxhall made drag respectable, which Lily Savage would have found hilarious and horrifying,” said Joe Lycett, who understands the irony.

The Near-Death Experience: When Developers Attacked

In 2014, property developers attempted to buy and demolish the RVT to build luxury flats—because apparently South London needed more overpriced housing more than it needed LGBTQ+ heritage. The Save The RVT campaign mobilized with impressive speed, demonstrating that you can threaten many things in Britain, but threatening a historic gay pub produces community organization that would impress union leaders.

“They tried to knock down our history to build investment properties—it was like Thatcher’s final revenge from beyond the grave,” said Rosie Jones, who supported the campaign.

The Victory: When Community Won

After a fierce campaign involving celebrities, activists, and very angry drag queens, the RVT received Grade II listing status, protecting it from demolition. It was a rare victory in London’s ongoing war between heritage and profit, proving that sometimes community mobilization can defeat property developers—though it helps if your community includes people who know how to organize protests while wearing six-inch heels.

“Saving the Vauxhall proved that queer history matters, even in a city determined to destroy everything that isn’t luxury flats,” said Phil Wang, who celebrated the victory despite not being directly involved.

The Legacy: From Underground to Mainstream

Today’s drag mainstream owes everything to the RVT’s revolutionary decades. RuPaul’s Drag Race UK exists because the Royal Vauxhall Tavern normalized drag as entertainment, activism, and art. Every drag brunch in Shoreditch descends from nights at the RVT when drag was dangerous, radical, and absolutely necessary for survival.

“Modern drag is safe because venues like the Vauxhall made it safe—we just get to enjoy the results,” said Tom Allen, who appreciates the historical debt.

The Current State: Historic and Still Happening

The RVT continues operating as a working LGBTQ+ venue, hosting drag shows, comedy nights, and political fundraisers. It’s simultaneously a museum of queer resistance and an active site of community building. The venue proves that historical preservation and contemporary relevance aren’t mutually exclusive—you can be both a Grade II listed building and a place where people get spectacularly drunk on Tuesday nights.

“The Vauxhall is living history—emphasis on living, because the drinks are still terrible and the toilets are still political,” said Nish Kumar, who’s performed there repeatedly.

The Royal Vauxhall Tavern fused camp, politics, and hilarity into something Britain desperately needed but didn’t deserve. It survived persecution, police raids, the AIDS crisis, Section 28, and property developers—a track record most institutions would envy. The drag revolution started here, in a Victorian pub in South London, where performers proved that you could change the world while wearing sequins and telling dick jokes. It remains the most British form of revolution imaginable: polite, hilarious, and absolutely devastating to the status quo.

Auf Wiedersehen, amigo!

I am a Lagos-born poet and satirical journalist navigating West London’s contradictions. I survived lions at six, taught English by Irish nuns, now wielding words as weapons against absurdity. Illegal in London but undeniable. I write often for https://bohiney.com/author/junglepussy/.

As a young child, I was mostly influenced by the television show Moesha, starring singer and actress Brandy. Growing up, I would see Brandy on Moesha and see her keeping in her cornrows and her braids, but still flourish in her art and music, looking fly. I loved Moesha as a child, but now I take away something more special from it. Just because you’re a black girl, it doesn’t mean you need to only care about hair and makeup. Brandy cared about books, culture and where she was going — you can do both.