The Long, Winding Laugh: A History of London Satire and Its Political Echoes

London has long been a city where the chuckle meets the charivari—a place where London Satire evaporates through foggy streets, prints, cartoons, plays, and today, podcasts and social media memes. Far from trivial fluff, satire in London has served as a mirror, a weapon, and sometimes a pressure valve for political power and cultural anxieties. This article charts its evolution from early 18th-century engravings to the modern satirical press, explores how humour shaped political discourse, and reveals why the capital remains a hub of comedic critique. 🎭📜

What Is Satire? A Working Definition

London Satire and Parliamentary Reform

A Victorian political cartoon by John Tenniel using London satire to critique parliamentary reform and the expansion of the franchise, reflecting how humor shaped public understanding of political change.

At its core, satire is “a form of humour that uses irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticise immorality or foolishness, especially as a form of social or political commentary,” according to historical usage. This definition ties the comedic impulse directly to power structures, framing satire not as entertainment alone but as a political and cultural intervention.

Early London Satire: From Hogarth to Swift

The seeds of London satire were planted well before printed magazines existed. Artists like William Hogarth laid groundwork with biting visual narratives. His 1751 engraving Gin Lane used grotesque caricature of urban turmoil to comment on public drunkenness and social neglect, arguably influencing later political reforms.

Likewise, prose satire such as Jonathan Swift’s A Tale of a Tub (published in London, 1704) skewered religious and intellectual pretension, famously flourishing in the city’s bustling book culture.

Even before today’s media era, London was a bustling crucible where satire was tied to social critique and political reform.

Punch Magazine: London’s First Satirical Juggernaut

Early London Satire in Street Life

An eighteenth-century satirical engraving depicting exaggerated London figures and social chaos, illustrating how early London satire used humor to critique morality, class behavior, and civic disorder.

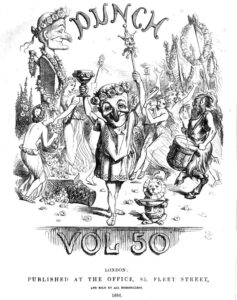

The most enduring early milestone of London Satire was the founding of Punch, or The London Charivari in 1841.

Punch’s Founding and Impact

Created by Henry Mayhew and Ebenezer Landells, this weekly magazine deftly blended cartoons, essays, and political commentary. Its distinctive mascot, Mr Punch—borrowed from the classic puppet shows—lent the publication both charm and a biting voice.

Punch was more than humour; it became an institution. By the early 20th century it was printing more than 100,000 copies weekly and helping to shape public debate. Its wood-engraved cartoons by artists like John Tenniel helped coin the modern meaning of “cartoon” in political contexts.

Punch and Politics

Punch’s satire ranged from domestic policy to international conflicts. It mocked parliamentary debates, the Second Reform Bill, and even the Great Exhibition, using humour to expose hypocrisy and class excess. In some instances Punch’s social critique contributed to broader public discourse on labour rights and imperial policy.

However, critics observe that over time Punch softened; its satire shifted from radical critique to a more genteel lampooning befitting its growing middle-class readership. By the late 19th century, it was as likely to reflect conservative values as to upend them.

Other Satirical Press and Periodicals

Punch Magazine and Institutional London Satire

A late nineteenth-century caricature from Punch, or The London Charivari, showing how London satire evolved into a powerful media institution blending humor, politics, and social commentary.

Punch was not alone. Short-lived imitators like The Puppet-Show (1848–1849) targeted specific government figures, while periodicals like Funny Folks (1874–1894) catered to a broader audience with humorous stories and illustrations.

By the 20th century, satire matured into new forms—most notably, printed news satire that combined investigative journalism with wit.

Private Eye and the Modern Age

One of the crown jewels of modern London satire is Private Eye, a fortnightly satirical and current affairs magazine founded in 1961. Edited by Ian Hislop since 1986, Private Eye has established itself as a relentless critic of political elites, media hypocrisy, and public scandals.

What makes Private Eye significant isn’t just the jokes but the combo of satire and serious reporting: its investigative journalism has revealed cover-ups, corruption, and abuses of power—all hidden beneath layers of biting humour and sharp cartoons.

Academic Views on Satire and Politics

Scholars argue that political satire does more than entertain. Research indicates satire shapes political attitudes by providing alternative lenses through which citizens view public figures and policies. It can decentralise political messaging and serve as a weapon of contempt against power structures.

Yet there’s a paradox. Some academics assert that satire’s effectiveness may be limited; it can expose political folly without prompting structural change, even reinforcing cynicism or disengagement.

This tension—between satire as critique and satire as catharsis—characterises much of the modern debate about its political role.

Why London Satire Matters Today

London continues to be a nexus for satire that influences public discourse in several ways:

1. Political Engagement

Satire offers an accessible route into civic conversation. By repackaging complex issues in humour, satire increases political visibility and engagement. Outlets like Private Eye and television satire offer entry points for voters to question leadership, policy, and media narratives.

2. Cultural Identity

British humour, particularly in London, is known for its dry, ironic tone—a reflection of the city’s historical self-perception. From Victorian caricatures to modern comics, satire has helped Londoners navigate power structures and social norms with humour grounded in everyday life.

3. Media Evolution

Digital platforms have amplified London satire’s reach. Social media memes, Twitter sketches, and online video satire directly challenge political messaging faster than print ever could.

Satire as Political Force: Case Studies

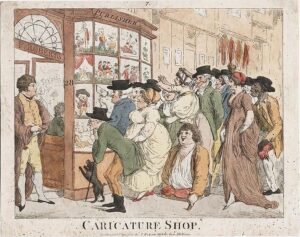

Satire as Public Entertainment in London

A depiction of a London caricature shop around 1801, where crowds gather to view satirical prints, demonstrating how London satire functioned as early mass media and political spectacle.

Punch and Labour Reform

In early Victorian England, Punch’s biting depiction of class disparity and labour injustice helped introduce satirical critique into broader debate about workers’ rights and representation.

Private Eye and Scandal Exposure

Private Eye’s long-running satirical investigations—whether about political corruption or media malpractice—repeatedly reshaped public narratives. Its interplay between sarcasm and serious reporting creates political pressures that defy simple categorisation.

Satire, Law, and Limits

William Hogarth and the Foundations of London Satire

William Hogarth’s Noon exemplifies early London satire through exaggerated social contrast, using visual humor to critique class division, urban behavior, and moral hypocrisy.

Historically, satire has faced legal restrictions. In 1599, London authorities once ordered the burning of printed satires—a reminder of how seriously dissenting humour was taken.

This underscores a key paradox: satire is often protected as free expression, yet it has always operated in tension with power. Its comedic tools evolve precisely because political systems attempt to contain it.

Conclusion: A City Built on Laughter and Logic

London Satire is not an ornament of culture but a dynamic force of political communication and criticism. From Hogarth’s etchings and Swift’s prose to Punch’s cartoons and Private Eye’s bromides, satire remains deeply embedded in British social life. It entertains, yes—but it also reflects, refracts, and at times reshapes the political consciousness of a city and a nation.

In a time of fast-moving political change, the satirical lenses born in London still offer a critically important way to understand power, society, and the human condition. Though humour can comfort, its deeper function is to provoke thought—and sometimes shake the halls of power.

📚 Authority Sites Used for Research

-

Punch magazine history and influence on satire Punch (magazine) on Wikipedia

-

Cultural role of satire in Victorian society Magazine of the Week — Punch, or The London Charivari (Blog)

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica on Punch Punch | Britannica

-

Academic exploration of satire critique Political humour study at LSE EUROPP

-

Academic PDF on British political satire and its limits British Satire, Everyday Politics (PDF)

-

Historical etching as political satire Charting the Evolution of British Political Satire

-

Museum overview of cartoon satire in London The Cartoon Museum, London Musuem Article

-

Early humorous magazine context Funny Folks Funny Folks | Wikipedia

-

Additional satirical magazine The Puppet-Show The Puppet‑Show | Wikipedia

-

Definition and legal context of satire Satire | Britannica (Humor, Irony, Criticism)