London Once Tried to Fix Society by Taking Away Beer and Adding Buildings

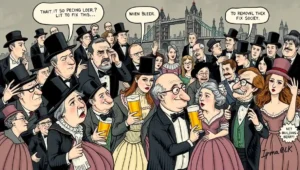

Victorian London looked at widespread poverty, social collapse, and gin-fuelled chaos and decided the obvious solution was sobriety, lectures, and better signage. This was not a modest ambition. This was a city that believed it could architect morality, zone virtue, and brick-by-brick nudge human beings toward goodness by removing alcohol and replacing it with coffee, billiards, and deeply sincere self-restraint.

Modern Londoners doing Dry January like to think they are participating in a bold experiment. In truth, they are reenacting a city-wide rehearsal for joyless improvement that once involved millions of people, hundreds of buildings, and a moral confidence that could only exist before Netflix.

Victorian reformers genuinely believed that if you took away beer, people would immediately become better versions of themselves. Not slightly better. Entirely reformed. Poverty would retreat. Crime would apologize. Men would go home early and discuss ethics. London would be saved, not through wages or housing or sanitation, but through abstinence and tasteful architecture.

The Grand Experiment in Removing Fun

The Temperance Movement did not just discourage drinking. It replaced the entire social ecosystem. Pubs were bad, so alternatives had to be built. Alcohol corrupted leisure, so leisure had to be purified. The result was a parallel London where you could still be entertained, insured, housed, healed, and morally approved of, as long as you promised never to enjoy yourself too much.

Concert halls appeared that proudly offered music without alcohol, a concept that sounds harmless until you imagine it enforced. Coffee taverns rose to provide social spaces where nobody slurred, laughed too loudly, or made questionable decisions that later became anecdotes. Billiard halls existed where games could be played without beer, proving that even in the nineteenth century, reformers understood compromise.

Hospitals, Insurance, and Moral Hotels

Hospitals took in only the sober. Insurance companies insured only the virtuous. Entire hotels advertised themselves as alcohol-free, which is like opening a swimming pool that bans water but promises reflection.

The ambition was staggering. Reformers did not just want people to stop drinking. They wanted people to become better by design. Buildings would guide behaviour. Layouts would correct instincts. Fountains would defeat beer.

Architecture as a Moral Lecture

Nowhere is this clearer than at The Old Vic, a building that today hosts plays full of human messiness but once stood as a monument to sober uplift. When it was transformed into the Royal Victoria Coffee Music Hall, audiences were offered purified entertainment. No alcohol. No moral risk. Just culture, responsibly consumed.

The phrase purified entertainment should still send a small chill down the spine. It implies that entertainment left to itself becomes impure, which history suggests is largely true, but also necessary.

Water Fountains as Moral Infrastructure

Elsewhere, water fountains were installed to provide an alternative to beer. This was not about hydration. This was about symbolism. Water was moral. Beer was failure. Thirst was the gateway through which vice entered the working classes, and reformers believed a well-placed fountain could close that door forever.

This confidence in infrastructure has never left London. Today, we still believe bollards will fix crime, lanes will fix people, and signage will fix behaviour. The Victorians simply believed it harder and with less irony.

The Sober Parallel London

At its height, the Temperance Movement created a fully operational alternative city. You could sleep, socialize, play, attend events, and quietly judge others without ever encountering alcohol. It was London, but with the volume turned down and the joy strictly supervised.

Temperance billiard halls thrived because even the most committed reformer understood that you cannot simply remove pleasure. You have to reroute it. Games were allowed. Snacks were permitted. Fun was tolerated as long as it behaved itself.

These spaces reveal an enduring truth about humanity. People will accept almost any ideology if it still includes games and refreshments. Remove both and the movement collapses.

The Solemn Processions of Moral Victory

The processions of the London Temperance League marching solemnly through public spaces were not protests so much as mobile reminders. They were saying, look at us, we have conquered ourselves. The real target was not drinkers. It was doubt.

The Confidence of Moral Certainty

Victorian reformers genuinely believed they could fix society if enough people signed a pledge. Millions did. This was not fringe activism. This was one of the largest social movements in English history, powered by the belief that personal restraint could substitute for structural change.

Alcohol was blamed for poverty. Drink explained violence. Gin caused misery. Remove gin and everything else would naturally fall into place.

This belief survives today in subtler forms. We still love solutions that ask individuals to fix systemic problems through personal discipline. Drink less. Spend better. Be mindful. Walk more. Everything else will resolve itself.

The Temperance Movement was not wrong about alcohol causing harm. It was wrong about alcohol being the only problem. London did not become just by becoming sober. It became sober and then carried on being complicated.

The Relapse of History

Most Temperance buildings have disappeared. Some were demolished. Others quietly absorbed into modern life. A few survive as architectural ghosts, their moral purpose invisible beneath coffee chains and ticket queues.

The irony is unavoidable. Buildings designed to eliminate drink now exist in a city where alcohol is marketed as wellness, sobriety is a subscription model, and moral certainty is sold as a lifestyle choice.

London’s Choice: Compromise Over Certainty

Dry January feels hard because it is meant to be temporary. Victorian teetotalism tried to make it permanent. Londoners eventually chose compromise. Pubs returned. Beer survived. Life continued in its usual untidy way.

Every surviving Temperance building stands as a reminder that London has always swung between excess and restraint, often within the same street. The city never truly chose sobriety or indulgence. It built both, tested them, and then went for a pint.

And that, more than any pledge or fountain, may be the most honest architecture London has ever produced.

Lowri Griffiths brings a distinct voice to satirical journalism, combining cultural critique with dry humour. Influenced by London’s creative networks, her writing reflects both wit and discipline.

Authority stems from experience, while trust is built through transparency and ethical satire.