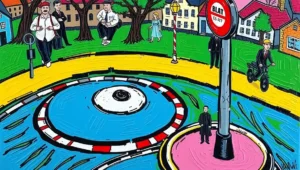

Britain Declares It Has “Turned a Corner,” Admits It Keeps Arriving at the Same Roundabout

The government confirmed this week that Britain has officially “turned a corner,” a major milestone announced so frequently that transport experts are now investigating whether the country is trapped inside a policy roundabout with decorative shrubs and no visible exits.

“This is a moment of real progress,” a minister said, smiling with the confidence of someone who has delivered this line before. “We are moving forward.”

When asked where forward leads, the minister gestured broadly and suggested the public “trust the direction of travel,” a phrase that has replaced maps entirely.

According to internal documents, the corner in question is not a sharp turn but a gradual curve, designed to feel dynamic without causing sudden change. Officials confirmed the same corner has been turned several times already, each time accompanied by a new slogan and a refreshed colour palette.

A leaked diagram shows Britain travelling in a smooth loop labelled “reform,” “stability,” “delivery,” and “lessons learned,” before arriving once again at “turning the corner.” Engineers reportedly recommended installing signs, but were told signage might imply accountability.

Public reaction has been cautiously weary. “I remember this corner,” said Alan, 63, from Stoke-on-Trent. “We waved at it during the last crisis.”

Polling suggests the phrase still performs well despite overuse. Sixty percent of respondents said “turned a corner” makes them feel briefly hopeful, 28 percent said it means nothing, and 12 percent said it sounds like something you say when you’ve reversed into a hedge.

Experts say the metaphor has endured because it suggests improvement without specifying distance. “A corner implies change,” explained Professor Miriam Holt, a linguistics specialist. “But it doesn’t promise arrival. It’s the perfect political vehicle.”

Behind the scenes, civil servants are trained to deploy the phrase strategically. One guidance note advises using it during interviews when numbers are inconvenient. Another suggests pairing it with “early signs” and “cautious optimism” to create what one aide called “a mood rather than a metric.”

Opposition figures criticised the announcement, arguing that the government has been turning the same corner for years. Ministers rejected this, insisting each turn is distinct. “This is a different corner,” a spokesperson said. “This one has context.”

Local authorities responded pragmatically. Several councils confirmed they have aligned their messaging to the corner narrative, with regeneration plans now described as “approaching a corner” and bin collection improvements labelled “corner-adjacent.”

In the business community, reaction was mixed. Some welcomed the stability of familiar language. Others expressed concern that the economy may be stuck in a conceptual cul-de-sac. “You can’t grow indefinitely by circling,” said one economist. “At some point, you need a straight road.”

International observers were polite but puzzled. One EU diplomat said Britain’s corners appear “remarkably consistent,” adding that in most countries, turning a corner eventually reveals a new street. “In Britain,” he said, “it seems to reveal another press conference.”

Despite scepticism, officials remain upbeat. “The important thing is momentum,” said the minister. “We’re not standing still.”

Asked how long it would take to reach the destination beyond the corner, the minister paused. “That depends,” they said, “on how many more corners there are.”

As the announcement concluded, Britain carried on, indicators flashing, engine idling confidently, circling once more past the same familiar landmark. The corner, patient as ever, waited to be turned again.

Alan Nafzger was born in Lubbock, Texas, the son Swiss immigrants. He grew up on a dairy in Windthorst, north central Texas. He earned degrees from Midwestern State University (B.A. 1985) and Texas State University (M.A. 1987). University College Dublin (Ph.D. 1991). Dr. Nafzger has entertained and educated young people in Texas colleges for 37 years. Nafzger is best known for his dark novels and experimental screenwriting. His best know scripts to date are Lenin’s Body, produced in Russia by A-Media and Sea and Sky produced in The Philippines in the Tagalog language. In 1986, Nafzger wrote the iconic feminist western novel, Gina of Quitaque. Contact: editor@prat.uk